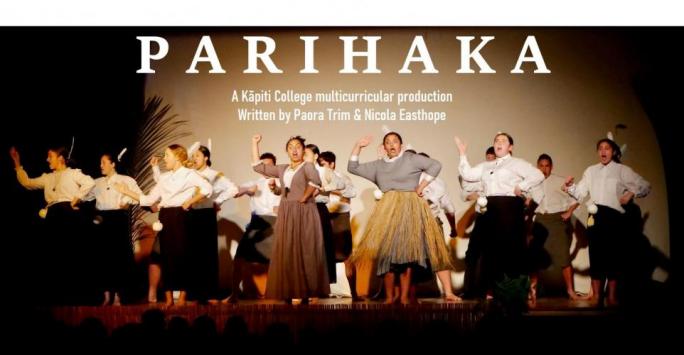

‘Parihaka’ – A Kāpiti College Multi-Curricular Production

Reviewed by Te Aniwaniwa Black.

Kāpiti College’s multi-curricular production ‘Parihaka,’ written by Paora Trim and Nicola Easthope, is a fictional account of real life events based on the invasion of Parihaka, November 5th, 1881 and also known as ‘Te Rā o te Pāhua’ or ‘The Day of Plunder.’

In the intimate ambience of the Coastlands Theatre, the first scene opens with the dulcet tones of Karl Jenkins’ ‘Benedictus’ – the effect of a live orchestra and choir raising the audience’s expectations of what was to come – as the villagers begin to take the stage in various forms of activity, greeting one another, preparing flax, laughing and playing games. Benedictus which simply means ‘blessed’, providing a fitting metaphor for a village that is itself at peace in the paradise of Parihaka, immediately prior to the events that would be forever etched in the hearts and memories of Taranaki Māori.

The scene captures a community committed to the peaceful teachings of Te Whiti o Rongomai (Te Whiti) and Tohu Kākahi (Tohu), foreshadowed by the threat of a military invasion as tensions reach breaking point between the people of Parihaka, who choose passive resistance to protect their ancestral lands (by removing the pegs of land surveyors and ploughing land marked for farming) against the land-grabbing colonists.

The karanga of a ‘kuia’ (all the roles are played by students) and opening kōrero between the villagers reminds us that this is a time when te reo Māori was still the predominant language among the people of Parihaka. This is embraced with most of the story told in te reo with just enough English for non-speakers of Māori, provided by Maioha, who translates for her husband, Haeata, the orders of soldiers to leave Parihaka or be forcibly removed, and her attempts to negate their assertions that the land belongs to the government; the powerful ‘Titia ki te pono’ capturing the frustration of the villagers but also reconfirming their faith in the peaceful doctrine of their leaders.

We meet Lydia, the wife of Lance Corporal Frederick Simpson who writes of her experiences living in Taranaki to her sister in England, reflecting on the fertility of the land and the ease with which any plant will grow – the health of their livestock and the joy of eating food grown and raised on the bountiful lands of Taranaki. While the dialogue between Minister of Native Affairs, John Bryce and his counterpart, William Rolleston in Scene 3, provides the context for which the military invasion would later be justified by government.

Scene 4, Te Rā o te Pāhua retells the devastating events on Nov 5th, 1881; the men of Parihaka Pā are arrested and in the next scene, held without trial in Dunedin in caves so cold and harsh, sickness and death are inevitable under such extreme conditions and this is Haeata’s fate which Maioha foresees in a dream.

In the last two scenes we ride the waves of despair, grief and loss as Maioha and the villagers struggle without their men folk, to deal with the reality of being landless and homeless. The return of those who survived imprisonment and the promise to rebuild together their lives is a turning point that brings hope.

The recital of ‘Little Potato’ in scene 7, provides deep insight into the bond that exists now between Ngai Tahu and Parihaka descendants.Mention of the Toroa (Albatross) acknowledges the wearing of the white plume of Toroa feathers by the descendants of Parihaka today as a visible symbol of Te Whiti and Tohu’s legacy, of their whakapapa to Parihaka and their enduring resilience.

Although Te Rā o te Pāhua took place over a century ago, this production and its characters remind us of the relevance and significance of this part of our country’s history, the importance of remembering the lessons of our past and the need for understanding. It is especially significant for us on the Kāpiti Coast, as the new performing arts centre was opened and named ‘Te Raukura ki Kāpiti’ by Taranaki iwi representatives – reinforcing a deep connection that goes back to 1987 with the opening of the first marae at Kāpiti College under Taranaki tikanga.

Finally, in his closing acknowledgements, Kāpiti College Māori teacher, Paora Trim, paid tribute to the Taranaki elders for whom Parihaka is more than a place, but rather, a way of life that can flourish anywhere. It is clear that the legacy of Tohu and Te Whiti is alive and well at Kāpiti College and will continue in the future to influence generations to come.

Te Aniwaniwa Black

Editor’s Note: There is a youtube film of the Kāpiti College production of Parihaka in two parts:

Part 1.

https://youtu.be/7g7qIWkE00Q

Part 2.

https://youtu.be/ZKfxuG7ToKI