Porirua Lunatic Asylum was designed to give the mentally ill a refuge from the cruel world, a place providing fresh air and moral guidance on an idyllic rural site. Patients say it was nothing more than a prison.

Kirsty Johnston reports for RNZ as part of the In Depth Special Projects series.

When Beverly Wardle-Jackson drove through the gates of the former Porirua Hospital for the first time in 50 years, she had one thought: Burn it down.

“I’ll be honest with you – that’s how I felt. It’s left such a terrible scar on my mind,” she says. “It was an evil, evil place.”

Wardle-Jackson, who now lives in Christchurch, returned to Wellington to take a tour of the old psychiatric facility ‘for a look’ – maybe in the hope it would provide some kind of closure on her time there as a teenager.

But as she was led through the long, wooden dorm of its only remaining building, listening to the curator give the hospital’s history, Wardle-Jackson says she realised the visit was a mistake.

“I just felt like standing there and saying, you’re just telling lies you’re not telling the truth as to what went on,” Wardle-Jackson told the RNZ investigative podcast Nellie’s Baby. “They did terrible things to people there. It was a nightmare experience, it really was.”

Wardle-Jackson’s story of forced institutionalisation, given as evidence to the Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, gives a rare window into the murky world of psychiatric treatment at Porirua Hospital, from a patient perspective.

Until the Commission began in 2018, most of the institution’s history came from former staff who worked at the hospital, or the officials who governed it.

‘Problem’ girls

Wardle-Jackson’s evidence is important for a second reason – it’s also one of the only stories on record from a woman in psychiatric care. Female patients were much less likely to come forward to the inquiry in general, and Wardle-Jackson was the only public testimony from Porirua.

“The majority of survivors currently registered with us are male,” the commission’s website says. “But women and girls have distinct reasons for being placed in care, and have suffered distinct types of harm.”

A fear of “moral delinquency” in the 1950s and 60s saw hundreds of girls placed in care for what we would now consider extremely spurious grounds. This included teenage pregnancies or reporting sexual abuse. Māori girls were more likely to be placed in care, simply because they were Māori. “Bad behaviour” was also a reason for being locked up.

“Girls seen as difficult to control could also be labelled mentally unwell and sent to psychiatric institutions… previously institutionalised girls were more likely to remain in, or return to, institutions because they were viewed as ‘risky’ or in need of further containment.”

Wardle-Jackson was among that cohort of girls considered “a problem”. She had been removed from her parents as a child, because they were too poor to take care of her and her siblings, and sent to a succession of children’s homes throughout the early 1960s.

When she was 14, she was sexually assaulted by an Anglican vicar. Shortly afterwards, the head of the girls’ home where she lived had her assessed at Wellington Hospital’s psychiatric ward. From there, she was sent to Porirua. It was June 1967.

“I remember being taken to Porirua Hospital in an ambulance,” Wardle-Jackson told the Commission of Inquiry in 2019. “When I saw the sign to Porirua Hospital, I was frightened. We had referred to places like Porirua as nut houses, funny farms or looney bins. I wondered what I had done to deserve being sent here. I was only 14 years old. I remember the tears flowing again. Nobody cared about me or wanted to help me.”

On that first day, Wardle Jackson says she was held down by nurses and stripped naked, drugged, and put in a room alone.

She was threatened by staff with further violence as she stepped out of line. When she did something the staff didn’t like (usually this was trying to run away) she was attacked or punched by staff, and put in seclusion, she says. This was a dirty, dark, cold cell with nothing but a mattress on the floor.

Her days largely consisted of sitting in the day room, bored, smoking endless cigarettes. But the tedium was also tense. At any point, it could be punctuated by a random act of violence from another patient, so Wardle-Jackson was always on high alert.

Despite her suffering, there was no one to complain to, Wardle-Jackson says. She was a ward of the state, they didn’t seem to have anywhere else for her to go, and there was no clear pathway to being discharged. No one even explained why she was in Porirua – there was no diagnosis, no committal process.

“To this day, I’ve never had an explanation as to why when I was 14 years old, they shoved me out there and, you know, were prepared to forget about me,” she says.

Wardle-Jackson was only released from Porirua after she escaped and hitch-hiked, pregnant, to Auckland in 1973, where a judge took one look at her file and let her go. He couldn’t understand why she had been in a psychiatric ward in the first place.

Photo: RNZ / Cole Eastham-Farrelly

Photo: RNZ / Cole Eastham-Farrelly

Photo: RNZ / Cole Eastham-Farrelly

Photo: RNZ / Cole Eastham-Farrelly

A place for ‘incurables’

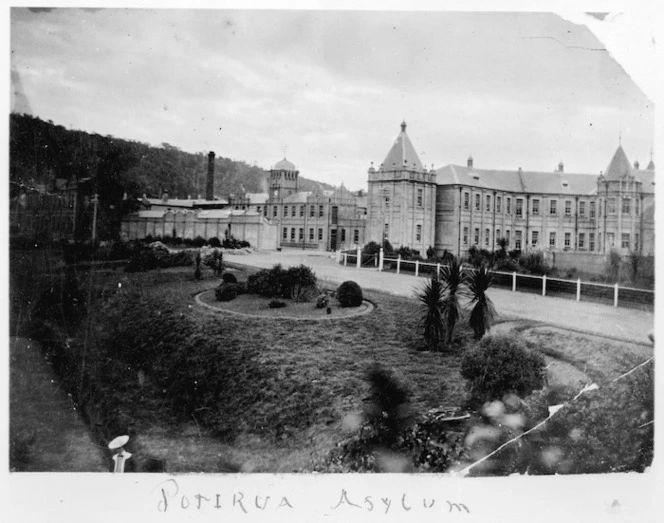

Porirua Lunatic Asylum was opened in 1887. It was designed to ease overcrowding at Wellington’s other asylum, Mt View in Karori, and to provide a rural site for “incurable” patients away from public curiosity – as well as an opportunity for them to work outdoors. The idea was that the patient labour would enable the hospital to become somewhat self-sufficient.

At that time, the asylum’s huge, damp, gothic building housed not just the mentally unwell but also the intellectually disabled, alcoholics, the homeless and the senile. The construction, complete with dormitories, day rooms and single rooms, could accommodate 513 patients. By 1900, it was full, but patient numbers kept rising.

Partly, this was due to the rise of the pseudo-science of eugenics and the policies it led to – including the 1911 Mental Defectives Act, which gave the state power to classify, and then segregate those deemed dangerous and deviant, to prevent the “infection” of the public and stop the “feeble-minded” reproducing. (It also replaced the term “asylum” with “hospital” and “lunatic” with “inmate”.)

According to Dr Hilary Stace, an academic specialising in eugenics, psychiatric hospitals often weren’t run by experts, but by those who had returned from war and needed jobs. This meant the care of vulnerable people was left to a combination of eugenicists – who saw the patients as sub-human – and veterans traumatised by violence. Combined with the moral panic, this led to dire circumstances, Stace says.

“There was a lot of this idea that people needed some sort of discipline, and there was this historic idea of asylum. But the ‘asylum’ idea really was less about asylum and more about locking away.”

To deal with the increased numbers of the diagnosed “mentally defective” that needed housing, an annex was built at Porirua, and then several more modern “villas” – wooden buildings housing 40-50 people, spread about the grounds, designed to be less intimidating than the huge asylum.

But despite the extra rooms, by the 1940s, the asylum was severely overcrowded, housing 1500. When the original building was destroyed in 1942 by an earthquake, it was replaced by a further 11 villas. This still didn’t help the overcrowding – by 1965 there were 300 excess patients. In some villas the beds were only ten inches apart, with “primitive” bathing facilities, unsanitary toilets and kitchen, and freezing sleeping blocks.

Throughout the 50s and 60s and into the 1970s, patients were treated either as workers – frequently bribed with cigarettes to do jobs – or as “animals”, one patient recalled in the book Out of Mind, Out of Sight, a history of Porirua Hospital. They had no clothes of their own, but were forced to share from a communal closet, there was nowhere private to take visitors, there weren’t even doors on the toilets.

“I had the feeling that the staff thought that we were rubbish…in that situation you became an animal. You were treated like an animal and you became an animal. You had no identity to those people in charge of you, you were just human flotsam and jetsam.”

That unidentified patient’s experiences echo that described by renowned New Zealand author Janet Frame, who spent time in mental hospitals in the South Island in the 40s and 50s. In her autobiography ‘An Angel At My Table” Frame wrote: “There was a personal, geographical, even linguistic exclusiveness in this community of the insane who yet had no legal or personal external identity – no clothes of their own to wear, no handbags, no purses, no possessions but a temporary bed to sleep in with a locker beside it, and a room to sit in and stare, called a dayroom. Many patients confined in other wards of Seacliff had no name, only a nickname, no past, no future, only an imprisoned Now.”

‘Concentration camps came to mind’

But it wasn’t just the patients who believed their treatment was inhumane. In evidence to the Royal Commission, Dr Olive Webb, a clinical psychologist who worked at another of New Zealand’s asylum’s, Sunnyside, compared the way the patients were treated during this period to the World War II concentration camps used by the Nazis – another group of eugenicists.

“The first day that I spent there I was there early in the morning and these men were — got up from their beds, shuffled into that lobby, stripped naked, they were then marched, or sort of herded really, through the main villa and through the end of the day room, into this large bathroom that had multiple shower heads, they were showered en masse by nursing staff who were wearing rubbers and gumboots.

“Concentration camps came to mind.”

Webb says control of the patients was achieved through intimidation, and seclusion. It was common for the hospitals to hire “burly men” to keep the patients in check – particularly in the male wards.

Paul Hickey was placed in Porirua at age 15. He had a brain injury after being hit by a truck, and doctors decided he needed psychiatric care – against his family’s wishes. Paul’s sister, Catherine Hickey told the commission that Paul’s treatment in Porirua was violent and dehumanising.

“When Paul first was placed in Porirua he was virtually stripped,” she says.

“They cut his long hair, which he used to hide his head injury, and took his possessions. He became so fearful he refused to shower because he couldn’t protect himself.

“Mum saw Paul with black eyes and evidence that he was regularly beaten up. He had unrelenting physical injuries. He told her that the staff would round up the patients and hose them down with cold hoses. His radio was stolen, he could no longer listen to his beloved music. His watch was stolen too, along with any money that he had.”

Shock treatment as punishment

The former Porirua patients who gave evidence to the Commission described the hospital like a black box – once you went in, it was impossible to get out. And once you were in, the doctors had full control of your life and your treatment.

From the 1940s, this treatment included the use of electro convulsive therapy, or ECT.

Despite being introduced as a therapy, patients at Porirua said they experienced ECT more as a punishment.

Cherene Neilson-Hornblow told the commission that her brother Sidney Neilson became unwell with supposed schizophrenia as a teenager, and was committed at Porirua. As soon as he arrived he was given electric shock treatment, or ECT. His family was horrified – they never gave consent.

Sidney Neilson described his experience to the commission in a 2019 hearing.

“It was horrible. Used to wake me up in the morning in bed and put my pyjamas on, they put me into a single room and we used to have a cup of tea and toast in a room,” Neilson said. “Would be about four or five of us, and we’d walk out and go sleep on the beds…Then the doctors would come around, the psych doctors and nurses come around and they told me to lay on the bed and they gave me treatment, shock treatment. I was trying to fight it, you know. I did fight it, yeah. It was horrible eh, it was hell. Worse than prison.”

Patients say particularly during the earlier periods, they were given ECT without anaesthetic. In the book Out of Mind, Out of Sight, one woman said she remembered being lined up, handing in her hairclips and false teeth and then lying down on the bed for “her turn”.

“You were really knocked out by shock treatment in those days – you didn’t get an injection first – and I really thought they were killing me,” she said.

Former Porirua medical superintendent John Hall – who was also quoted in Out of Mind, Out of Sight – said the doctors had a legal right to administer ECT, and they operated on that right without question.

It wasn’t until a strong public backlash that the use of ECT was reduced in the 1980s, and patient consent was taken into account. It is still used and considered effective for some patients.

Waiting on an apology

Porirua Hospital was finally closed in the 1990s as part of the wider deinstitutionalisation process, which saw psychiatric patients and the disabled supported to instead live in the community, or in smaller facilities such as group homes.

In 1987, the hospital’s last remaining building, the long wooden dormitory known as F-ward, was converted into a museum housing memorabilia from the hospital. This includes a seclusion room, preserved with the claw marks in its walls and doors from patients, straight jackets, medicine jars and ECT machines.

For former patients like Beverly Wardle-Jackson, however, the hospital is more than a relic from the distant past. It’s a site of living trauma. She still has nightmares about it, still sees the faces of the patients she met there, including her friend who was institutionalised at age 12, and remains institutionalised now.

Wardle-Jackson says the public need to hear what went on at Porirua, from those who experienced it, to prevent such horror happening ever again. As well as giving evidence to the Commission, she wrote a book about her experiences in state care, called In the Hands of Strangers.

She is still waiting for a personal apology from the state. The commission is due to report back in mid-2024. Whether the government will then attempt to atone for what happened at Porirua Hospital, either with an apology or compensation for survivors or both, is yet to be decided.

For more from the RNZ In Depth Special Projects series: https://www.rnz.co.nz/programmes/in-depth-special-projects